- Home

- J. R. Roberts

Death in the Desert Page 2

Death in the Desert Read online

Page 2

Still no answer.

“I rode into town yesterday. I can see what happened here. Are you sick?”

He waited, but there was still no answer. Whoever it was could have been watching him from any window. Or they were already in another part of town.

He continued across the street to Eclipse.

“How you feeling, boy?” he asked, rubbing the horse’s nose. “You’re taking this very well. Actually, I’m taking it pretty well. I could be getting pretty sick in a little while, and maybe a doctor could help me. But if I go to find a doctor, I could make a lot of the people sick. So tell me, big boy, what do I do?”

Eclipse just stared at him. He had no answers. Maybe that was because the disease apparently did not affect animals. In addition to seeing no dead horses, Clint had not seen any dead dogs or cats, or livestock.

Well, one thing he could do was find the person who seemed to be the only survivor in town. Or else he could sit down and wait to die, but that was never his style.

“Where are you?” he called out, mounting up. “I just want to help you.”

He rode Eclipse through town, yelling like he was the town crier.

• • •

In the end, he depended on Eclipse to entice her out. He went back to the café where he or she had eaten last, left the big gelding right outside. Eclipse attracted a lot of attention. He was hard to resist, especially for a child.

Clint found a place from where he could watch, and settled in to wait.

It didn’t take long.

FOUR

As Clint watched, a little girl with blond hair came out of one of the buildings, looked around carefully, then started walking toward Eclipse. She was wearing a soiled yellow dress, her bare legs and arms also in need of a wash. Her hair was as yellow as the dress.

She walked carefully toward the horse, still looking around for Clint. He was sure that at first sight of him, she would break and run. He needed to sneak up on her once her attention was completely on Eclipse.

He knew the effect the big gelding had on people, especially children. He also knew that Eclipse would do nothing to harm the child. The Darley Arabian may not have liked being touched by strangers, but he’d never do anything to a child who tried to pet him.

The girl moved closer to the big horse. When she got around in front of him and extended her hand, the horse bent his head so she could reach him. She was now completely entranced by him, and it was time for Clint to make his move.

He came out the door of the hardware store and sneaked across the street to her side, then started moving slowly toward her.

Eclipse lowered his massive head enough for the child to rub his nose. As Clint got closer, he realized the girl was talking to the horse.

“You’re a good boy, ain’tcha?” she said. “You’re a good boy, and a big boy. How’d you get here? Where’s the man who rode you?” She rubbed his nose harder. “Can you take me out of here? Can ya? I’ll bet if I could get on your back, I could ride you away from here.”

Clint was behind her now. He said, “I can help you ride him.”

She whirled around, wide-eyed, stared at him, and then tried to run. He was too fast for her, and grabbed her.

“Let me go, let me go!” she shouted, trying to kick him.

“Take it easy,” he told her. “Come on now. We have to help each other.”

She continued to struggle.

“Don’t you want to ride my horse?”

She struggled a bit more, than stopped and looked up at him. She had the bluest eyes he’d ever seen, a beautiful but grubby-looking little girl.

“He’s—he’s yours?”

“That’s right.”

“I can ride him?”

“Sure you can.”

“Can you—can you take me away from here? I don’t like it here.”

“I don’t much like it either,” Clint said, “but I can’t leave just yet. When I do, though, I’ll take you with me. Where are your parents?”

“My mother and father . . . they left me here.”

“Left you? But why?”

“I was sick, and they weren’t. They said I was going to die and they had to leave.”

“Who told them you were going to die?”

“The doctor.”

“What’s your name?”

“Emily.”

“How long ago did they leave, Emily?”

“I—I ain’t sure. Mister . . . are you gonna die? All the grown-ups, they either left, or died. There’s lots of dead bodies in this town.”

“I know,” he said. “I found them. Look, Emily, we have to help each other. If I let you go, do you promise not to run?”

She thought about it a moment, then said, “Okay, I promise.”

He released her. She immediately turned, but instead of running, she reached for Eclipse’s nose again.

“What’s his name?” she asked.

• • •

They went into the café where he’d discovered the hot frying pan with the bacon grease.

“Will Eclipse be all right alone out there?” she asked.

“He’ll be fine.”

“Will he get sick?”

“I don’t think so,” Clint said. “I haven’t seen any dead animals around here.”

He walked her to a table and they sat down.

“Emily, have you been taking care of yourself all this time? Since your parents left?”

“Yes,” she said. “When they left, I was in my bed. I think I slept for a very long time. When I woke up, I felt weak and thirsty. I—I got up, and got dressed and went looking for Momma and Papa, but I couldn’t find them. I couldn’t find anybody, except for dead people. So I made myself something to eat.”

“And you’ve been doing that ever since?”

She nodded. “Mama showed me how to cook so I could help around the house.”

“How old are you?”

“Ten.”

“Can you show me where you lived?” Clint asked. “Maybe I can find something there that will tell me how long your parents have been gone. Or where they’ve gone.”

“I can show you.”

“Is it far?”

“Not far,” she said, “if we ride.”

He smiled at her and said, “Let’s ride.”

FIVE

Clint put Emily in the saddle and walked alongside her so he could catch her if she fell off. She directed him this way and that until they came to a stop in front of a small, one-floor, wood-framed house.

“We lived in there,” she said, pointing.

“Okay,” he said, lifting her off Eclipse’s back to the ground, “show me.”

They walked to the front door, where she balked.

“Emily? Are there any . . . dead people in there?” he asked.

“N-No.”

“Then we can go in, right?”

“Y-Yes.”

“Are you afraid?”

“No,” she said, “I’m sad.”

She reached for his hand, grabbed it, and they went into the house together.

“Okay,” he said, “why don’t you sit on the sofa while I look around?”

“No,” she said, squeezing his hand, “I want to stay with you.”

“All right,” he said, “show me your parents’ room.”

“This way . . .”

She took him down a hall to a bedroom which obviously belonged to adults. However, it also looked as if it had been hit by a cyclone.

“I didn’t do it,” she said.

“Do what?”

“Make this mess,” she said. “I didn’t do it.”

“Oh, honey, I know you didn’t do this. Your parents obviously packed in a hurry.”

“Because they were a

fraid I’d make them sick?” she asked.

“Not you,” he said. “The disease.”

“But . . . what disease? Why didn’t I die?”

“Obviously,” he said, “you were immune to the disease.”

“Huh? What’s im-immune?”

“It means that while the disease killed a lot of other people, it didn’t kill you.”

“Is that why my momma and papa didn’t get sick? Because they was immune?”

“I think so. I think a lot of people were immune, and they decided to leave town.”

What they hadn’t done was try to warn travelers about the disease that had ravaged their town, or burn the town down, which was what they should have done. But if they had, they would also have burned up Emily.

“What’s your last name, Emily?”

“Patterson,” she said. “My name is Emily Rose Patterson.”

“Well, Emily Rose Patterson, let’s take a quick look around and see if your parents left anything that will tell me where they are. And then we’ll go and get something to eat. How’s that sound?”

“Good, I guess.”

“And you know what?” he said. “I’m a terrible cook. Maybe you could cook something for us to eat?”

She brightened at that.

“We could go to Flo’s Café,” she said. “I ain’t cooked for myself there yet. There’s bound to be a lot of food.”

“Good,” Clint said. “After we look around, we’ll ride Eclipse over to the café.”

“Okay!”

Still holding hands, they looked around the room, and then walked through the rest of the house. Clint found nothing that would tell him where the parents had gone. He also did not find any mail that would tell him where some of their relatives might live.

They left the house. He put Emily back in the saddle, then mounted behind her. After that, she directed him to Flo’s Café.

SIX

Emily knew her way around town very well. She easily guided Clint to Flo’s Café. They went inside to the kitchen, and once he saw how at home she was there and that she didn’t need any help, he went and sat at a table.

Obviously there were many citizens of Medicine Bow who had not succumbed to the disease and had left town. This was a good sign for him. It was possible that he’d be one of those people who was immune, but it would take a while before he’d be comfortable that he had survived.

He also wondered if, after a reasonable amount of time went by, the citizens would come back, or if they had given up on the town and started over somewhere else. If they came back, perhaps Emily’s parents would come back with them. However, if they had started over somewhere else . . . well, there was no guarantee that the whole town had stayed together. Maybe they would have split up, rather than be reminded of the disease every time they looked at one another.

Soon the smells from the kitchen wafted out to him. If those aromas were any indication, Emily really did know how to cook.

When she came out, she was carrying two plates teeming and steaming with eggs and vegetables.

“The meat is bad,” she told him. “But there were plenty of eggs and vegetables left behind.”

He frowned. The steaks he’d prepared for himself had tasted kind of funny, but he’d assumed that was a result of his own cooking skills. Was it possible he’d eaten bad meat? If the disease didn’t take him, would the bad meat kill him?

She sat across from him and said, “Go ahead, eat your food.”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“You didn’t tell me your name,” she said, as if scolding him. “My daddy always says people should introduce themselves.”

“I’m sorry,” he said. “My name is Clint Adams.”

“Mr. Adams, what’s your horse’s name?”

“Well, you can call me Clint, Emily,” he said. “And the horse’s name is Eclipse.”

“Eclipse,” she said, was if tasting the word. She nodded. “I like that.”

“I’m glad. By the way, these are the best eggs I’ve ever tasted.” It was true, they were the best eggs he’d ever had . . . without meat.

“Thank you. I know my daddy likes his eggs with ham or bacon, and sometimes steak, but I just ate the last of the good bacon. Sorry. Like I said, the rest of the meat’s no good anymore.” She wrinkled her nose.

“Oh,” she said suddenly, “I forgot the coffee.”

Coffee? He hadn’t smelled coffee. She left the table and hurried into the kitchen, then came out walking very carefully with a mug of coffee.

“Thank you,” he said, accepting the mug. She ran back to the kitchen and returned with a glass of water for herself. She sat back down to eat. Clint wasn’t sure about the water, which was why he’d been drinking beer or whiskey. He sipped the coffee. It was hot, but weak, although that didn’t really matter.

“It’s very good,” he lied, putting the cup down. “You really are good in the kitchen, aren’t you?”

“My momma says I am.”

The child obviously loved her mother and father. How, he wondered, could they have left her behind without knowing for sure that the disease had taken her?

“Clint?”

“Yes?”

“How come you and me ain’t dead?”

“Well,” he said, “I guess we’re just able to resist the disease, Emily. But from what you told me, you did get sick, right?”

“Oh, yes.”

“But you didn’t die,” he said. “So I suppose I might still get sick . . .”

“And die?”

“Maybe,” he said. “I hope not.”

“Can’t we leave before you get sick?”

“No, honey,” he said. “First we have to make sure I don’t have the disease. We don’t want to take it with us to another town, do we?”

“I suppose not,” she said, leaning her elbow on the table with her face in her hand. “But when can we leave?”

“Soon,” he said. “I’m still feeling pretty good, so we may be able to leave soon.”

She brightened. “We have the whole town to ourselves”—and then her expression soured—“but it kind of smells bad.”

“All those dead people should have been buried,” Clint told her. “The people must have been in a real hurry when they left here.”

“I was in bed,” she said, “but I could hear people shouting outside . . . and then it got quiet.”

Clint figured if the townspeople left en masse, he should be able to pick up some kind of trail once they got outside of town, depending on how long ago they left.

“What should we do after we eat?” she asked.

“I think we’ll look around town some more,” Clint said, “see if we can find some supplies that we’ll need for our ride.”

“Clint?”

“Yes.”

“I’m glad I’m not alone anymore.”

“So am I, Emily,” he said. “So am I.”

SEVEN

Before looking for supplies, Clint decided to go to city hall and see if he could find any notes that might indicate where the people had gone. Also the telegraph office.

City hall was first. Thankfully, they did not come across any more dead bodies.

“I ain’t never been in city hall before,” Emily said, her eyes wide.

“Why not?” Clint asked.

“Well . . . that’s where the mayor works.” She said it in hushed tones.

“Emily, can you tell me if the mayor got sick?”

“I don’t know,” she said.

“Okay. We’re going to go to his office.”

Her eyes widened even more. “The mayor’s office?”

“That’s right.”

He took her hand and they entered the building. The mayor’s office was on the second floor, in the back, rather tha

n in the front, where he’d have a window overlooking the street.

When they got inside, Clint saw that it was a very large office. It had to be, to fit the large teakwood desk.

“Oh my,” Emily said, looking around.

“Emily, you have a seat while I look around.”

“All right.”

She got up into one of the wooden chairs that faced the mayor’s desk. Clint got behind the desk and sat down. There were some papers strewn across the top of it. He went through them, but there was nothing to tell him where the townspeople had gone. He started going through the drawers and Emily covered her mouth with her hands.

“What?” he asked.

“You’re going through the mayor’s drawers,” she whispered.

“Well,” he said, “the mayor’s not here, so I think we’re all right.”

“Okay,” she whispered.

He continued to go through the drawers, scanning papers, but there was nothing helpful.

“Okay,” he said, sitting back. “I think we’re finished here.”

“What do we do now?”

“We’re going to the telegraph office.”

“Oh, good,” she said. “I like that place.” She got down from the chair. “I like the clackety-clack that the key makes.”

“The key?”

“The telegraph key,” she told him. “Didn’t you know it was called that?”

“Well, yes, I did know that,” he said. “Come on. Let’s go.”

He took her hand and they left the office, and the building.

“Which way is the telegraph office, Emily?” he asked.

“That way,” she said, pointing. “A few blocks. Can I ride Eclipse?”

“Of course.”

He lifted her up into the saddle and then they walked to the telegraph office.

“Do you want to come inside?” he asked.

“Yes,” she said. “Clackety-clack.”

“Clackety-clack,” he repeated, and lifted her down.

They walked inside the office, which looked as if it had been ransacked. There were yellow pieces of paper all over the floor, and desk.

“I don’t hear the key,” she complained.

The Dead Ringer

The Dead Ringer The Devil's Collector

The Devil's Collector Five Points

Five Points Ticket to Yuma

Ticket to Yuma Ace in the Hole

Ace in the Hole The Gunsmith 385

The Gunsmith 385 Bandit Gold

Bandit Gold Shadow Walker

Shadow Walker Bitterroot Valley

Bitterroot Valley The Last Buffalo Hunt

The Last Buffalo Hunt Unbound by Law

Unbound by Law Blood Trail

Blood Trail The Two-Gun Kid

The Two-Gun Kid Cross Draw

Cross Draw The Counterfeit Gunsmith

The Counterfeit Gunsmith Copper Canyon Killers

Copper Canyon Killers Hunt for the White Wolf

Hunt for the White Wolf The Valley of the Wendigo

The Valley of the Wendigo Message on the Wind

Message on the Wind Red River Showdown

Red River Showdown The Sapphire Gun

The Sapphire Gun The Dead Town

The Dead Town Kentucky Showdown

Kentucky Showdown Wildfire

Wildfire Louisiana Stalker

Louisiana Stalker The Deadly Chest

The Deadly Chest Standoff in Santa Fe

Standoff in Santa Fe Anatomy of a Lawman

Anatomy of a Lawman Riverboat Blaze

Riverboat Blaze The South Fork Showdown

The South Fork Showdown The Man with the Iron Badge

The Man with the Iron Badge Let It Bleed

Let It Bleed The Gunsmith 387

The Gunsmith 387 The Pinkerton Job

The Pinkerton Job Bad Business

Bad Business Fort Revenge

Fort Revenge The Town Council Meeting

The Town Council Meeting Forty Mile River

Forty Mile River Showdown in Desperation

Showdown in Desperation Out of the Past

Out of the Past Virgil Earp, Private Detective

Virgil Earp, Private Detective Straw Men

Straw Men Clint Adams, Detective

Clint Adams, Detective The Omaha Palace

The Omaha Palace The Killing Blow

The Killing Blow The Vicar of St. James

The Vicar of St. James The Legend of El Duque

The Legend of El Duque Red Water

Red Water Bandido Blood

Bandido Blood East of the River

East of the River Under a Turquoise Sky

Under a Turquoise Sky One Man's Law

One Man's Law Deadly Fortune

Deadly Fortune Crossing the Line

Crossing the Line To Reap and to Sow

To Reap and to Sow The Gunsmith 386

The Gunsmith 386 The Death List

The Death List The Lady Doctor's Alibi

The Lady Doctor's Alibi The Governor's Gun

The Governor's Gun A Different Trade

A Different Trade Dying Wish

Dying Wish Death in the Family

Death in the Family The Clint Adams Special

The Clint Adams Special Ball and Chain

Ball and Chain Way with a Gun

Way with a Gun The Golden Princess

The Golden Princess Fraternity of the Gun

Fraternity of the Gun The University Showdown

The University Showdown Pariah

Pariah Two for Trouble

Two for Trouble The Three Mercenaries

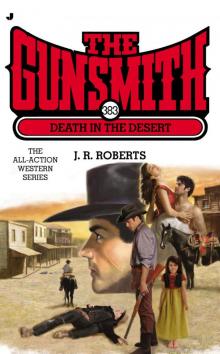

The Three Mercenaries Death in the Desert

Death in the Desert